Let's Encrypt uptime is 98.8% for some

As I was collecting reliability data for several PKI systems, I included Let’s Encrypt as it’s

by far the biggest PKI system I was aware of. It provides its status data and its history at

https://letsencrypt.status.io

and here’s my analysis of its production systems.

While Let’s Encrypt publishes data of all its incidents, it is rather vague in terms of the

impact of particular incidents. There is little information like a fraction or an actual number

of failed requests, who were the impacted users, or if a particular event was limited to a

certain geographical region. Despite this shortcoming, the results presented here represent a

rather interesting peek behind the curtain of a hugely successful online service and I welcome

any comments to further improve its accuracy.

Another reason why I wanted to look at the reliability of Let’s Encrypt certificate issuance was

to find out, whether there’s a good enough reason to use an independent / external monitoring

service. I advocate the use of our https://keychest.net service (an HTTPS/TLS monitoring service

with automated certificate discovery) as it detects failures of certificate renewals.

The question is, whether there is a sufficient justification for that, i.e., failures happen

often enough to have a negative impact on Let’s Encrypt users. I dare say that this analysis

builds a case for such external monitoring.

Planned updates and maintenance

Let’s Encrypt Boulder — the technology powering the certificate management is new — the GitHub

repository shows first commits at the very end of 2014. When you combine this with the rocket

growth of its utilization and the number of certificates it manages, you do expect frequent

updates of the software.

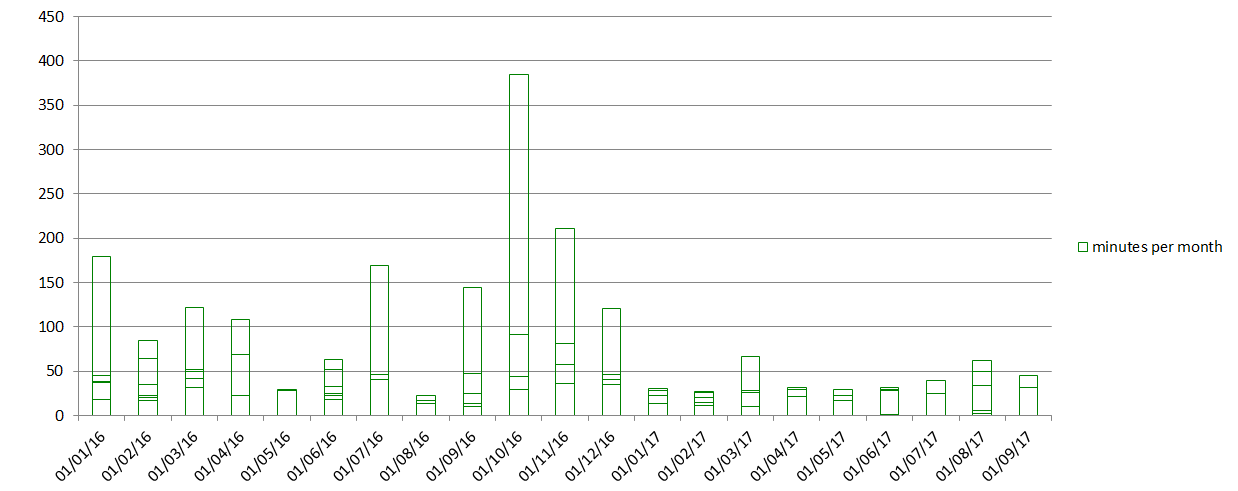

Multiple updates are stacked so that the chart above shows the number of minutes reported as

spent on updates every month. The records of Let’s Encrypt status show that its team aims for

regular updates to be done on Thursdays at 5pm GMT. While I can see mostly weekly intervals,

one or two “cycles” were skipped occasionally. Most of the updates were successful as I counted

only 3 rollbacks during the 20 month period.

Multiple updates are stacked so that the chart above shows the number of minutes reported as

spent on updates every month. The records of Let’s Encrypt status show that its team aims for

regular updates to be done on Thursdays at 5pm GMT. While I can see mostly weekly intervals,

one or two “cycles” were skipped occasionally. Most of the updates were successful as I counted

only 3 rollbacks during the 20 month period.

An important observation here is that updates benefited from the HA configuration of Let’s

Encrypt validation and issuance servers. Updates are described as “rolling” updates where the

second server was only updated once an update on the first server was successfully completed.

What I find interesting though is that regular updates represent the only circumstance, where

the reliability of Let’s Encrypt benefited from its two server configuration. Almost all

incidents impacted both production data centers. I find it remarkable if that was really the

case in terms of the quantitive impact of incidents as well.

Full disruptions

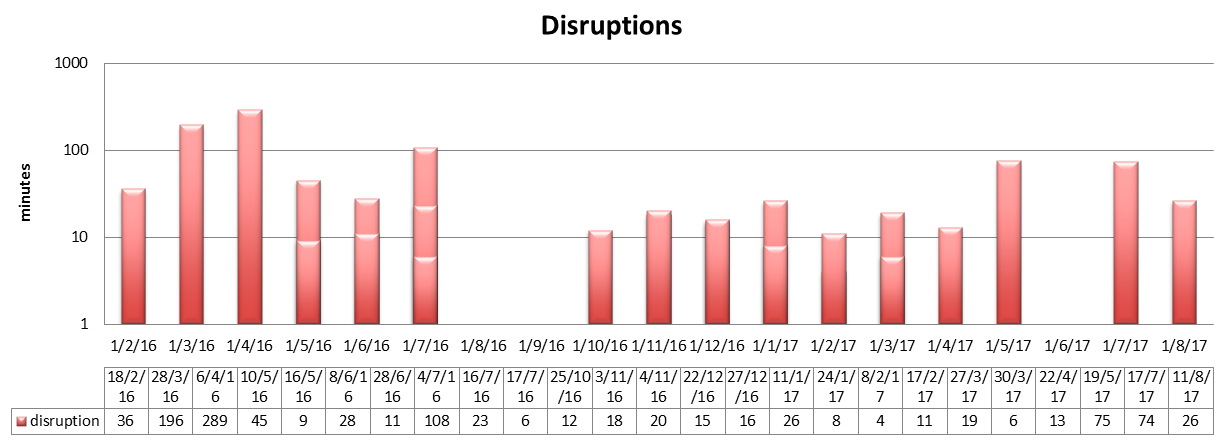

Now, when I say full, I’m not at quite sure whether particular incidents were complete service disruptions. I did my best to separate partial and full disruptions, and I believe the results presented below are good enough for deriving some conclusions about the reliability of Let’s Encrypt.

Multiple disruptions per month are stacked. The time is shown on a logarithmic scale!

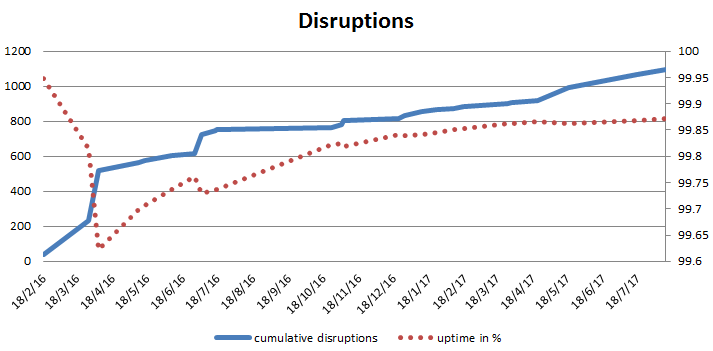

As the chart above uses a logarithmic scale. As it's not straightforward to convert minutes

into the uptime, I also add a cumulative graph, which gives a better idea of the system

reliability as usually measured. The red dotted line indicates overall uptime in % from the

beginning of 2016.

There seems to have been several incidents with a significant impact on the overall reliability

figures, but overall, the uptime has stabilized just under 99.9% in the last 6 months of the

operation.

That means that at least some users of Let's Encrypt experienced uptime of 99.9%, however, if you

were very unlucky, the actual uptime you experienced was much lower.

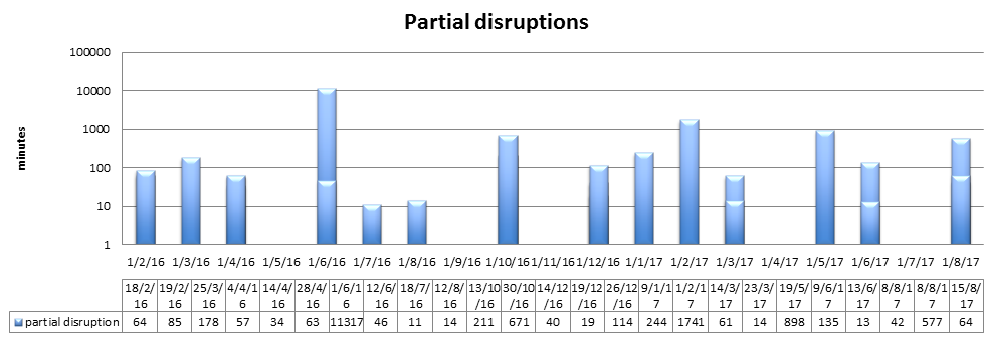

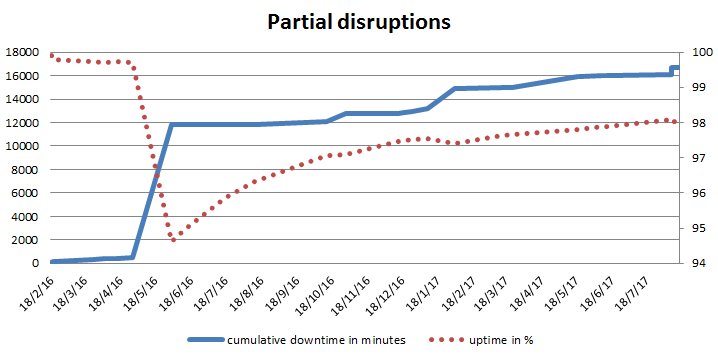

Partial disruptions

Partial disruptions are incidents, which were detected via increased occurrence of errors, or when some of the Let’s Encrypt users mentioned issues with certificate issuance.

It’s not surprising that the total duration and the number of “partial downtime” incidents are larger than for complete disruptions — you can notice that the chart above goes one order higher, even though it again uses a logarithmic scale. As a result, the overall up-time here was at around 98% at the end of September 2017. If you wonder what it would look like if we skipped the big incident in May 2016, the final up-time would go up to 98.8% in 2017 only.

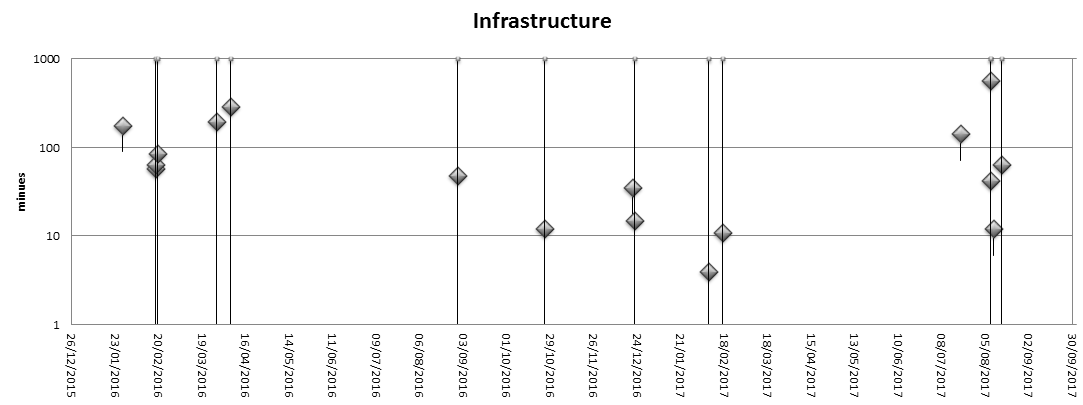

Infrastructure incidents

One issue I didn’t expect was down-times due to infrastructure problems, problems outside the core Let’s Encrypt systems. My expectation was that these events would not exist, or at least would stay hidden away from users thanks to the HA design of the system. Still, network disruptions, firewall incidents, DNS misconfigurations, and similar issues did happen and caused partial or even full disruptions of LE services.

Analysis

When I started, I expected the reliability of Let’s Encrypt to significantly improve after first

6 months or so. It doesn’t seem to be the case and service disruptions seem to occur regularly

over the whole analyzed period. Having said that, the uptime keeps improving, but it’s a long

way from 99.99% or higher, which you expect from commercial certificate providers.

The data also indicate that Let’s Encrypt doesn’t really gain as much benefit as I’d expect from

its high-availability configuration. Incidents usually show that both data centers with the

certificate issuing service are impacted at the same time. Related to this are also several

incidents when a bug in the software was discovered either during updates or shortly after —

possibly indicating deficiencies in testing.

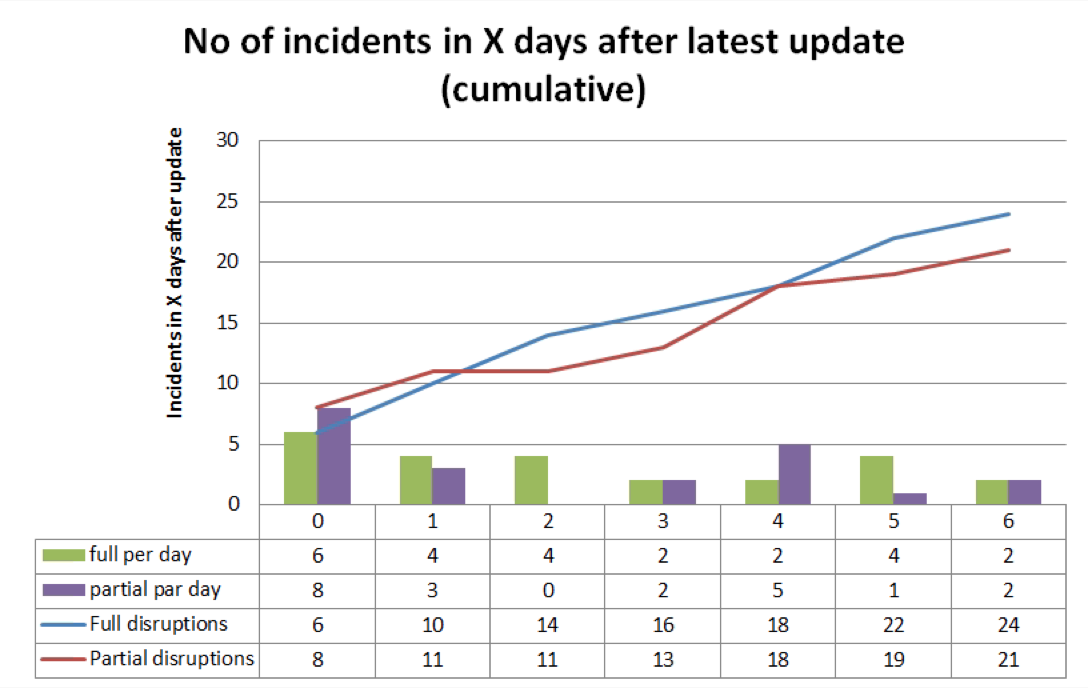

The chart to the left shows the number of disruptions (full and partial) in the days after

latest updates. You can see that the probability is skewed with the highest number of disruptions

happening on the day of an update. The remaining days between updates seem to have similar

probabilities of disruptions, although the data set is too small for any more detailed

analysis.

Based on the previous chart, I wonder if LE should consider some changes to the way updates are

executed and possibly if it is possible to strengthen the testing of new versions of the

software, like:

-

Installing a new version on a staging/test server (with test signing key) for 1–2 weeks first. This would receive “production” requests, with responses sent to a monitoring system, rather than back to users.

-

Staggered updates — update only one of the production servers with the latest release and in effect basically running 2 subsequent releases in parallel.

A pleasant surprise was the reliability of the OCSP service. The downtimes were limited to

infrastructure issues (networking, server time synchronization).

Having said that, there are many users who don’t benefit from this service as Chrome and Safari

browsers don’t do OCSP checks. This may get better with

OCSP stapling. However,

there are several practical operational aspects one should be aware of:

it adds some complexity to the server configuration;

the configuration must be resistant to short OCSP service outages; and

it increases requirements on the reliability of Let’s Encrypt OCSP service, where a few hours’ long disruption can cause a denial of service for your web server.

There were 2 significant OCSP outages in the last twelve months, they lasted 2+ and 9+ hours.

Initially, I thought that LE may need to re-configure the back-end system, to further minimize

common infrastructure, to increase the overall reliability of the service, but I’m not sure

whether it would have a significant impact. At the moment, it seems to me that most disruptions

can be prevented on the software level. This is an expected situation for a new system, still

under significant development.

A note about monitoring

I have been, and still am arguing my strong belief that external monitoring, which checks the

outcome (a server with valid certificate), rather than the renewal procedure (like whether a

certain process or a hook been started or invoked) is crucial for a reliable use of HTTPS / TLS.

It's not good to secure data between your web server and your users when there's no data to have

due to an expired certificate. We need a technology, which support the purpose of the internet.

That’s why we developed KeyChest.net and that’s why we offer

it for free to anyone, who tries to do the right thing and use HTTPS.

The whole process of renewing a certificate includes a large number of components and a small

change in any of them may cause a failure of a certificate renewal. Whether it is an update of a

Let’s Encrypt client or a change in the validation of requests. An example of the latter was a

change in the IP protocol preference from IPv4 to IPv6. Some LE users realized way too late

something went wrong, with their internet service providers (ISPs) to blame in some cases. One

wouldn’t expect an ISP to have a role in renewing LE certificates, but if they haven’t completed

or tested their IPv6 configuration, LE validations failed, HTTPS certificates didn’t renew and

web and application servers went down.

Maintenance and security

This is actually an aspect I didn’t have on my initial list, but it is an interesting one if you

are interested in building or operating your own high-security service.

The main document, which describes how Let’s Encrypt operates is a Certification Practice Statement

(ISRG CPS v2.0).

While this document mentions physical access to the Let’s Encrypt systems, it

doesn’t really cover remote access, which I suspect is the primary way of accessing servers for

updates, maintenance, etc. It is also an important aspect of the security of signing keys.

I expect Let’s Encrypt certification authorities (CAs) to use network hardware security modules

(HSMs) to provide physical security of signing keys. HSMs’ role is to prevent keys being leaked

and copied off-site. The very next threat is for the keys to be used without authorization as

today’s HSMs are network devices and their API can be used remotely.

I looked at the period of January 2016 to mid-September 2017 and Let’s Encrypt lists over 150

events in this period, with only a small number related to components outside the boundary of

the core LE infrastructure. This means that the ops team accessed the production systems almost

twice a week (every 4.2 days). A lot of visits or remote connections to a service, which is

supposed to show maximum possible security.

The security of the remote access and the strength of authentication, authorization, and access

control are thus absolutely crucial. The network security is just as important as the ability of

access systems quickly to resolve incidents. There is little information available about the

remote access to Let’s Encrypt data centers and I would really like this to change.

© 2023 KeyChest Inc. | Terms of Service | Privacy Policy | support@keychest.net | +1 (512) 696-1552 | World: +44-203-740-6998 | KeyChest (3.16.5-dirty)